Long before empires rose and fell like waves upon the plains of Bharata, there was a boy playing at the gates of Pundravardhan.

The other children ran when they saw the saffron-clad monks approaching, their footsteps echoing like thunder upon the earth. But the boy did not move. He stood still, intent upon his game—fourteen smooth stones balanced one upon another, defying gravity and chance. His name was Bhadrabahu, the son of the Brahmin Somsharma, though at that moment he was known only as a child with unblinking eyes and an uncommon calm.

When Acharya Govardhana, the fourth Shrutakevali, beheld him, he did not see a child. He saw the future of the Jain tradition. The fourteen stones were not toys—they were the fourteen Purvas, the deepest repositories of scriptural knowledge. Without hesitation, Govardhana took the boy by the hand, and with his parents’ consent, carried him away from household life into the discipline of renunciation. Thus began the making of the last man who would know the scriptures in their entirety.

Years passed. Bhadrabahu grew into silence, austerity, and divine perception. He became the fifth and final Shrutakevali, a vessel of complete knowledge in an age that was already beginning to decline. Where others reasoned, he knew. Where others feared, he saw.

Far to the north, in a village of peacock rearers, destiny was preparing another thread.

A Brahmin scholar named Chanakya stood watching a group of boys at play. One child sat elevated, issuing commands with effortless authority, while the others obeyed without protest. Chanakya’s sharp eyes narrowed. This was no ordinary boy. This was power waiting to be shaped.

Chanakya himself had been shaped by insult and fire. Born with a full set of teeth—a sign of kingship—his fate had been altered when his father broke them to save him from worldly rule. The prophecy changed: he would not be king, but he would create one. That prophecy burned brighter on the day King Nanda dragged him from the royal court, humiliated him, and loosened his knotted hair. Chanakya swore he would not tie it again until the Nanda dynasty was uprooted.

The boy from the village was named Chandragupta Maurya.

For years, Chanakya trained him—in war, governance, strategy, patience. Their first attempt failed; they struck the heart of Magadha too soon. Wandering in disguise, they learned their lesson from an old woman scolding her child for eating hot food from the center instead of the edges. Empires, like meals, must be approached from the periphery.

With patience, alliances, and calculated conquest, Chandragupta dismantled the Nanda rule and ascended the throne at Pataliputra. India stood united under a single crown for the first time. Chanakya ruled from behind the curtain, and Chandragupta ruled from the throne. Power flowed. Borders expanded. History took note.

But history was not done.

One night, in the quiet hours before dawn, Chandragupta dreamed sixteen dreams—strange, symbolic, unsettling. A serpent with twelve hoods rose before him. Images of decay, disorder, and loss passed through his mind like shadows. Though emperor of the known world, he felt suddenly small.

He sought Bhadrabahu.

The Acharya was living in a forest near Pataliputra, far from palaces and politics. When Chandragupta described his dreams, Bhadrabahu listened in silence. Then he spoke of the Pancham Kala, the age of spiritual decline. He spoke of famine—twelve years of it—foretold by the serpent’s twelve hoods, confirmed by omens he himself had seen.

Once, in Ujjayini, a baby had spoken from its cradle, urging him to leave. Another time, meaningless sounds—ba-ba—had revealed the number twelve through the science of omens. Knowledge had converged into certainty.

No king could stop this famine. No army could fight it.

That night, the empire began to loosen its hold on Chandragupta’s soul.

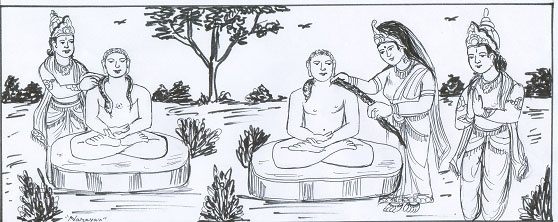

He handed the throne to his son, Bindusara, and removed the crown that had once symbolized absolute power. Taking Jain Diksha from Bhadrabahu, Chandragupta became the last crowned king in history to enter the monastic order.

When the famine began to cast its shadow across North India, Bhadrabahu made a decision that would divide history. To preserve the discipline of the monks and protect the sacred knowledge, he led nearly twelve thousand ascetics southward, away from the coming devastation. Chandragupta walked among them—not as emperor, but as disciple.

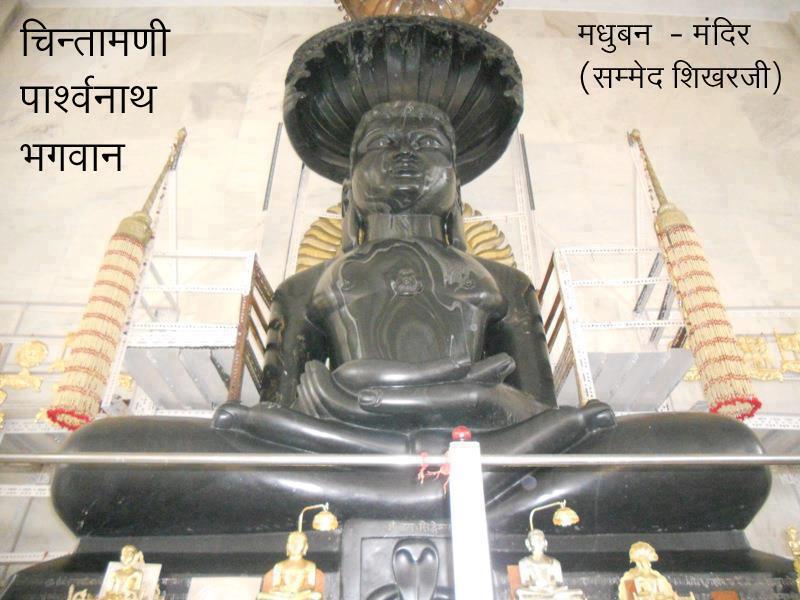

They reached a hill called Katvapra-giri.

There, Bhadrabahu heard an Akasavani, a divine voice informing him that his end was near. He instructed the sangha to continue further south under Acharya Vishakhanandin. He himself remained behind, entering a cave to begin Sallekhana, the final fast.

Chandragupta stayed.

He served his guru until Bhadrabahu’s final breath left his body in silence. When the last Shrutakevali passed from the world, the light of complete scriptural knowledge passed with him.

Still, Chandragupta did not return. He lived in the forests, practicing the harsh discipline of Kantara-charya, enduring hunger, solitude, and relentless meditation. Once, unable to find food that met monastic purity, he faltered—but only briefly. Faith carried him forward.

Years later, upon the same hill, Chandragupta embraced Sallekhana himself. The emperor who had once commanded armies now commanded only his breath. When it ceased, the hill was renamed Chandragiri, in honor of the king who chose renunciation over remembrance.

Chanakya, too, faded from the world of power. After shaping empires, he turned inward. Jain tradition remembers his final days as those of penance and withdrawal—some say through Sallekhana, others through tragic violence. However he died, his task was complete. The knot of his hair had been loosened long ago.

Thus ended an age.

An acharya who foresaw the storm, a strategist who carved destiny, and a king who laid down the world—three lives intertwined, not by ambition, but by renunciation.

And when the famine came, as foretold, the empire endured—but the lesson endured longer:

that true conquest is not of land, but of the self.

References: & Source Texts

This article is based on traditional Jain historical and spiritual sources describing the lives of Acharya Bhadrabahu, Chanakya (Kautilya), and Emperor Chandragupta Maurya, with particular emphasis on Jain charitra literature and oral traditions.

The primary narrative framework, events, and interpretations are drawn from the following authoritative Jain text:

Primary Reference

- भद्रबाहु–चाणक्य–चन्द्रगुप्त–कथानक एवं राजा कालिक वर्णन — Jain historical text by Mahakavi Radhakr̥t, edited by Dr. Rajaram Jain, documenting the Bhadrabahu–Chandragupta Maurya tradition. Available at:

https://jainworld.jainworld.com/JWHindi/Books/Sahjanand+Shastramala/Charitra/2015.424224.BhadrabahuCharitra1992AC6474.pdf

Contextual Tradition

This text belongs to the Jain Charitra (biographical) tradition, which preserves spiritual histories through a combination of scriptural memory, monastic lineage, and moral instruction. Events such as Sallekhana, Jain Diksha, and the migration to Shravanabelagola (Chandragiri) are presented in accordance with Jain doctrinal understanding.

Note to Readers

This article presents the Jain traditional account of these historical figures. Interpretations may differ from modern academic historiography, and the intent of this narrative is to preserve and share the Jain spiritual-historical perspective with fidelity and respect.